Welcome to Summer Skin School! A monthlong series of educational content, interviews and recommendations to help you and your skin thrive as the days get hotter. We’ll talk a lot about sun protection, of course, but also touch on other types of body care and summer-related skin concerns.

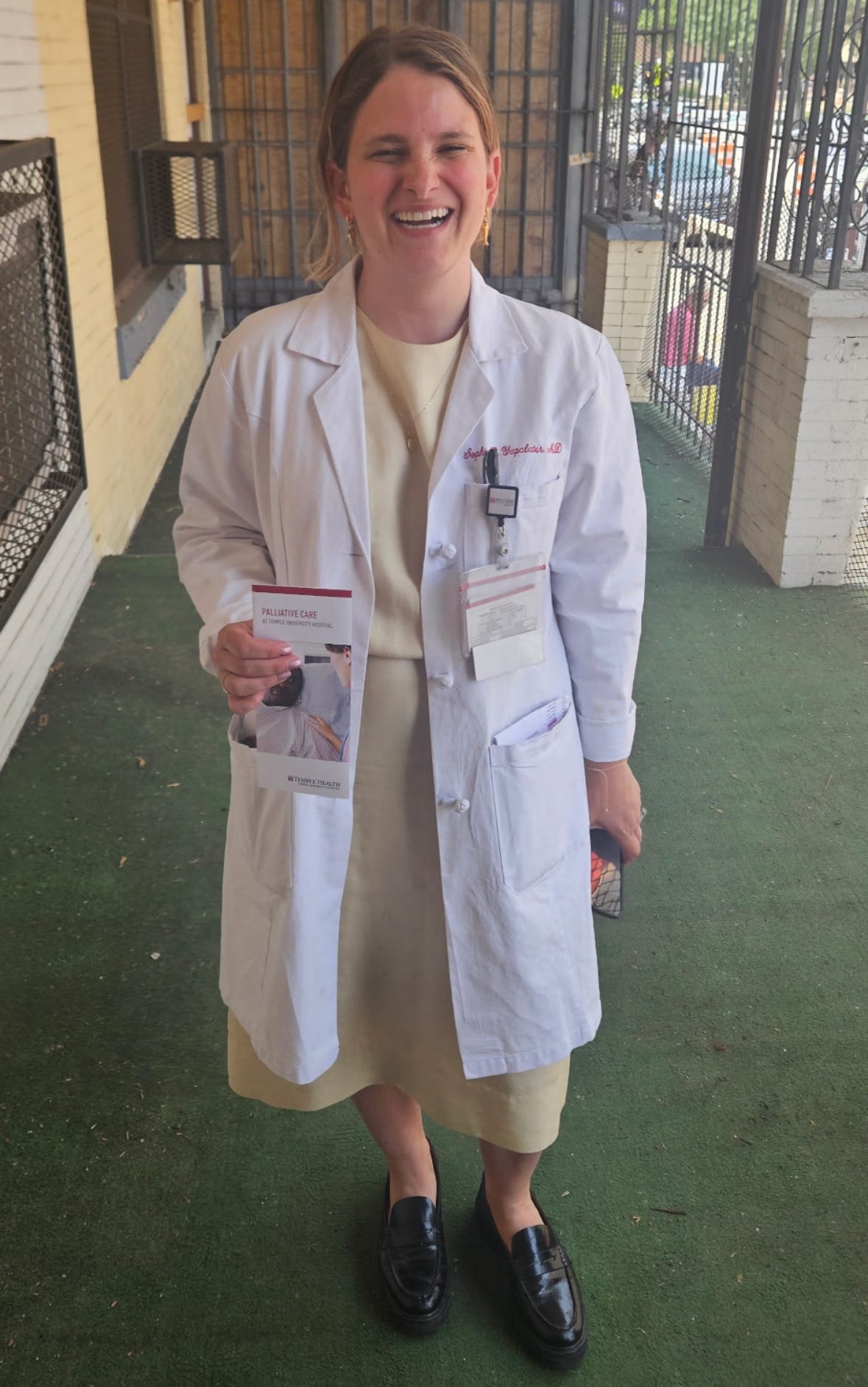

To kick things off, we have a special guest: my best friend, Dr. Sophia Yapalater, or as I call her, The People’s Doctor. She’s helped me and countless friends/family navigate health issues, interpret doctor-speak and generally just act like a normal, compassionate human who wants to help people with medicine. Hard to come by these days!

In her own words: “I uprooted my life a decade or so ago to pursue medical training so that I could answer my friends’ health questions but instead became so enthralled with end-of-life care and research that I’m now doing 4-5 years of palliative and critical care fellowship training. Whoops.” Because it’s important to brag about your friends, she attended medical school and completed internal medicine residency at the University of Pennsylvania, just finished up her palliative care fellowship and is starting another one next month at Duke University.

One of Sophia’s most special qualities is the way she is able to explain medical concepts in ways you can actually understand and feel empowered by, which is why as soon as I saw this tweet, I texted her that we needed to bring her in for some answers. And answers, we got! Time to figure out what is actually going on with vitamins––I learned so much and I promise you’ve never read an explanation like this.

What is a vitamin?

Great question!!

Vitamins are organic (made of carbon) compounds that are essential to the various functions of the human body. You may also hear them referred to as “micronutrients.” At this point in human evolution, our bodies can’t produce vitamins on their own (where is my flying car, etc), and thus, we need to get them from the outside world (see: bananas, and also the sun). They primarily act as “cofactors” or “coenzymes” in a range of essential biochemical processes.

Given that this is a gibberish science sentence even to me, I think the best way to think of them is as passwords: you need a specific password (vitamin X) to login to (initiate) your computer (biochemical reaction), and another one (vitamin Y) to get into your Substack account (different biochemical reaction), without which, you can’t blog (an essential cellular function, actually).

The father of vitamin science was a man named Cornelius Adrianus Pekelharing, who in the early 1900s noticed that animals who didn’t have milk in their diets had unexpected health issues. Later, another scientist named Casimir Funk isolated a concentrate from rice that seemed necessary to keeping up the good health of his pigeons. He named the concentrate “vitamine” because it seemed vital for life (vita) and was probably a compound called an amine. Researchers ultimately identified 13 of these vital substances and their specific functions, but they were only sometimes amines, so they dropped the E. And thus: vitamins.

I am telling you all of this primarily because the names Cornelius Adrianus Pekelharing and Casimir Funk are quite frankly too insane to keep to myself. The other reason is to show that the science around vitamins has been around for a long time, and the evidence behind what they do, and how much of them we need, is extensive and reliable. This is especially important in a climate fraught with health disinformation and direct to consumer companies offering to improve the quality and quantity of our lives via expensive lab tests and supplements, which we’ll talk about later on.

Before we keep going on this – are minerals a different thing? It seems like they’re always lumped together.

Minerals are another type of nutrient essential for various body functions. They are “inorganic,” which means they are not carbon-based or produced by plants and animals the way that vitamins are. They are usually lumped together with vitamins when we talk about nutrition because both are integral to physiology but come from the environment rather than being produced by the human body.

Minerals that you may have heard of before in the context of your health: calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, fluoride, iodine, iron, selenium, and zinc.

Wild. Okay back to vitamins: how many different kinds exist? What are their general functions?

There are 13 recognized essential vitamins, which are divided into two categories: fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins. These categories refer to how vitamins are stored in the body, and for how long. The fat-soluble vitamins are A, D, E, and K. They are stored in– surprise–fatty tissue (also known as “adipose”), for weeks to months. Water-soluble vitamins include the eight B vitamins and vitamin C. They dissolve once they enter the body, and thus we pee most of them out every day rather than storing them.

There is one outlier, Vitamin B12, which is water-soluble but is stored for months to years (!) in the liver. How vitamins are stored and gotten rid of has implications for how much of each vitamin we need on a day-to-day basis, and how long it takes to develop a deficiency.

Where do we get vitamins from? Specifically, how are they in both bananas and the sun?

Since we can’t make vitamins on our own, we need to get them elsewhere: primarily, in what we eat. Different foods have different vitamin content, hence the old adage of a “balanced and varied diet.” Not to worry, though, if there are certain foods you can’t (or don’t like to) eat, there is a lot of overlap between food groups. Plus, a lot of our food is “fortified” with micronutrients at this point– an evidence-based practice supported by the World Health Organization – thus, true vitamin deficiencies in the United States right now are rare.

There are many resources online with the best food sources for different vitamins (and minerals). I prefer the charts/tables intended for children because they are visually appealing and straightforward. I personally like the one pictured here. If you want this information directly from a medical source, Harvard Health has a good list.

The sort-of exception to the food rule is vitamin D, or “cholecalciferol.” It is naturally in a few foods, but is primarily synthesized by the body via sunlight (“are we human, or are we plant – Brandon Flowers” – Sophia Yapalater). For the nerds among us (myself, Jolie, maybe some of you), this is an extremely efficient cascade of biochemical reactions triggered by exposure to UVB rays, starting with the creation of cholesterol in your skin cells and ending with the synthesis of vitamin D in your liver. In other words: insane, and in my opinion: none of our business.

And now the question about vitamin D that everyone wants to know: what does this mean for sunscreen?!

Okay now I get to put my cute lil doctor hat on: please for the love of god wear sunscreen!!!!!!!

Sun-vitamin-D and food-vitamin-D are for all intents and purposes the same. Unfortunately, some bad actors in the wellness industry have perpetuated the myth that vitamin D is better absorbed via the skin, but the science simply doesn’t exist to support that. In fact, both forms are biologically inactive (aka: useless) until they are converted to an active form in the liver and kidneys. However, they differ in one very important way: only one of them is associated with higher rates of developing melanoma.

As you already know from our communal Skin Czar Jolie, limiting direct UV exposure via sunscreen and UPF clothing is fabulous for reducing risk of skin cancers. I, Hotline Skin’s new Health Czar (suck it RFK), can tell you that studies have consistently shown that typical sunscreen use does not generally lead to vitamin D deficiency. Even with the most optimal sunscreen use during periods of high UV exposure, vitamin D synthesis still occurs. Brief casual exposure to the arms and face, which most of us get day-to-day save for medical and surgical residents, is about equivalent to dietary intake of about 200 IU per day, which is a good third of the typical adult’s daily requirement!

There are a variety of populations at higher risk for vitamin D deficiency – babies, the elderly (we actually lose the ability to convert it to its active form effectively as we age), people who live in northern latitudes, and yes, people who rigorously use sun protection – which is why foods are routinely fortified with vitamin D to provide the other two-thirds of our daily need.

Plus, since the risk factors for vitamin D deficiency are well understood, your primary care provider knows when to screen for it!

So we get most vitamins through food, and a little bit from the sun. What about topically? If I use a serum with niacinamide daily, will that give me sufficient vitamin B3?

As a general rule, topically applied vitamins are not absorbed in sufficient amounts for biochemical benefit, though this is actively under study. This is primarily related to our robust skin barrier, which thankfully protects us from the various terrors of the outside world, and some of it is due to the unpredictability of environmental factors, such as temperature, that can impact molecule stability. However this is also one of the benefits of topical products – you generally get the skin-level benefit without high risk of systemic (full-body) toxicity.

A caveat: pregnancy skincare! Jolie interviewed me a while back about pregnancy-related skin care. Topical retinoids (a type of vitamin A) are not recommended for use while pregnant. While reliable data on topical retinoids in pregnancy is limited because we can't ethically do drug studies on pregnant people (guidelines are based on observational studies of isotretinoin/oral accutane) we err more on the side of caution because vitamin A toxicity can be catastrophic to a fetus.

There are a lot of vitamins and minerals that get thrown around in relation to skin. Can you tell us which ones are actually relevant?

Yep yep. I am not a dermatologist, but I can give some general principles on the main players. As a general rule, you don’t need oral supplementation of any of these, and the benefit is in topical application.

Vitamin A/Retinoids: Retinoids are a form of vitamin A that when applied topically, undergoes a series of biochemical reactions that increases signaling for epidermal cell turnover and collagen production. Please do not take oral vitamin A for acne without physician guidance!!

B vitamins: There are many! The B-vitamins play an important role in skin health by contributing to cell turnover, barrier function, and pigmentation. However, they are interdependent, and can also wreak havoc on your skin when out of balance with one another! I know this is something Jolie counsels her clients on, too – if you take a B-vitamin complex and notice you’re now breaking out, oftentimes they are related!

B3/niacinamide: B3 is a precursor to NAD+, a popular enzyme in wellness discourse that participates in a number of cellular reactions involved in DNA repair and oxidative stress. Topical application can reduce inflammation, help with hyperpigmentation, and support your skin barrier.

B5/pantothenic acid: important for skin cell turnover and regulation of oil production; topically, can help reduce sebum production and hyperpigmentation. (You’ll likely see panthenol on the ingredient list, which converts into pantothenic acid.)

B6/pyridoxine: man, this guy. Essential for collagen production in the right amount, but can be harmful to skin if taken in excess by causing extreme photosensitivity. Generally, if your kidneys work and you don’t have certain autoimmune diseases, you have enough. AFAIK, not generally used in skincare products, but often found in excess in B-vitamin supplements & energy drinks, which may contribute to skin issues.

B7/Biotin: essential for the function of keratinocytes, the cells that strengthen your skin barrier, hair, and nails. Biotin deficiency is exceedingly rare, so high doses will make your hair and nails grow faster and stronger, but can also lead to decreased levels of vitamin B5 (see above). Too much keratin + less regulation of oil production = comedogenic, which is why many people experience breakouts when taking biotin.

Vitamin C: a powerful antioxidant, which means that when applied topically, it can help neutralize “free radicals,” or environmental pollutants that we come in contact with, so it may help mitigate UV damage when used along with broad-spectrum sunscreen. There are many different derivatives of vitamin C that are used in skincare products, some of which can help with collagen synthesis, pigmentation and reducing dark spots.

Vitamin E: An emollient and humectant–when applied topically it helps soften skin, increase water absorption and retain moisture. It also is an antioxidant that may help protect against UV and other “free radical” damage and may have anti-inflammatory properties. On ingredient lists you will usually see it listed as tocopherol.

Vitamin K: Unlike the vitamins mentioned above, vitamin K doesn’t have a role in barrier repair/maintenance, pigmentation, or UV protection– instead, applied topically, it helps primarily with wound healing and reducing bruising.

Omega-3s/Fish Oil: Not a vitamin or a mineral, but an essential fatty acid that the body also doesn’t produce (it’s almost like we’re interdependent with our environment or something). Primarily implicated in cardiac and neurologic health, omega-3s also are known to play a role in skin health by reducing inflammation, improving epidermal hydration, regulating oil production, and supporting barrier function. Different Omega-3s (lineoleic acid, safflower oil, etc) are in some skincare products, but you very much should make sure you’re getting it in your diet!

Zinc: a mineral with antioxidant and immune system properties that helps protect skin from infection, reduces inflammation, and maintains barrier function. You’ll see topical zinc for prevention and treatment of diaper rash, moisture damage, and for UV protection (zinc oxide!)

How can we recognize vitamin deficiency? Does being tired all of the time mean I should get vitamin levels tested?

It would take many newsletters to comprehensively describe all 13 deficiency syndromes, but the key is that each one has a unique presentation related to the role that the vitamin plays in your body. Remember, they were first identified based on what health effects researchers observed when they were missing! Fatigue can certainly be a symptom, but is generally one of many in a deficiency “syndrome.” For example, vitamin B12 is integral to neurologic function, and thus deficiency is characterized by symptoms such as balance issues, muscle weakness, memory loss, and numbness and tingling of the hands and feet.

Routine testing of vitamin levels isn’t particularly useful for determining the root cause of symptoms like fatigue or brain fog. Fortunately, you only need relatively small amounts of each vitamin, and an even more minuscule amount of each mineral, to keep the machine running. And, because of fortification, it’s unlikely for someone to be deficient without having one of the well established risk factors that would already trigger screening labs.

However, a primary care provider does routinely test your blood counts and comprehensive metabolic function with lab panels that would clue them into a possible deficiency. A cool example of this imho is that when we do your blood counts, one of the values we look at is the size of your red blood cells (“mean corpuscular volume”) – if they’re too small, we know to test for iron deficiency (and some other serious diseases!), and if they’re too big, we know to check your folate and B12 levels.

I too wish there were an easy answer for my daily fist-shaking declaration of “why I am so tired,” but the reality is, a good chunk of it probably comes down to the profound exhaustion of living in a society that marginalizes people via systemic barriers to food access. I think a massive harm perpetuated by the modern-day wellness industry – and I don’t think this is an accident– lies in its failure to acknowledge that perhaps the biggest risk factor for vitamin deficiencies is poverty. In absence of a specific health condition or dietary restriction, not living in a food desert, and being able to afford groceries are arguably the most relevant protective factors against nutritional deficiency. And that sucks.

Can you also have too much of a vitamin?

Yes, you can! We talk about vitamin deficiencies a lot – and for good reason – but not as much about what happens if you have too much of one. I think this is because vitamin toxicity is a modern problem in that it really only comes from taking high-potency supplements. In recent years, with many of us searching for relief of functionally limiting symptoms, combined with an unacceptable shortage of primary care providers, there has been a rapid proliferation of social media health and wellness culture around supplements, marketing the benefit of taking a huge number of unregulated pills every day.

While lack of a vitamin or mineral prevents our bodies from starting or accelerating a biochemical process, too much of them can cause these processes to go into overdrive and sometimes cause harm. This is particularly true for fat soluble vitamins that remain in your body for a long time, and can more easily build up to toxic levels. Just as with deficiencies, effects of vitamin toxicities can range in severity from diarrhea and nausea all the way to organ damage.

Yikes. Is it ever safe to take supplements without consulting a healthcare provider?

Kind of. We generally don’t recommend taking them for prevention against developing chronic diseases, but individual doses of vitamins in a standard multivitamin formulation are generally safe in that they are well below the level of toxicity. There are also certain vitamin/mineral supplementations that we know are needed at various stages of life – for example, prenatal vitamins with folic acid when you are trying to conceive or are pregnant, and vitamin D drops for infants who are exclusively fed breast milk – that have standardized recommended quantities.

The issue is that supplements are considered a food product and are not regulated by the FDA. So, a company can say or put anything in them while making a bunch of health claims that are usually extrapolated from limited data – while also marketing their product as safer and more natural than rigorously tested medications. At best, this means that you’re spending your hard-earned money on a horse pill that just gives you indigestion. At worst, you’re inadvertently taking something that can cause lasting harm. Jolie reminded me of the recent controversy around Clearstem. They were marketing a supplement as “nature’s accutane” that contained 679% (!!!!) of a human adult’s daily vitamin A requirement. As many customers unfortunately learned, vitamin A toxicity can result in hair loss, vision issues, nausea, vomiting, and liver damage.

Here are four practical considerations for supplements:

1) Tell your healthcare provider everything that you take, including over-the-counter and direct-to-consumer, so that they can help you assess the risks, benefits, and possible interactions with other medications

2) Look at your labels: what is the percent of daily recommended value in the supplement? If it’s anywhere approaching the majority, it’s probably too much.

3) Check for overlap: If you’re taking more than one supplement that contains the same vitamin, the effect will be additive – eg, if you are taking two pills daily, each with 100% of your daily value of vitamin C, you’re taking 200%.

4) Consider the source: If someone is promising you that their specific supplement has superior bioavailability, better absorption, or is more natural or gentle than something else, they’re probably just trying to sell you something. Same goes for companies that do extensive lab testing and then link to a storefront from your results. A good healthcare provider will give you recommendations/guidance on indication and dose (eg, “pick a vitamin D supplement that provides you 600 IU per day since you never expose a single part your body to the sun”), but they shouldn’t be selling you any specific brand out of the front of their office.

See also: the laxative I needed to buy for my colonoscopy coming in a more expensive “sensitive stomach” version that only differs from the original in that it is…. Pink.

Thank you for explaining all of this!! Since you can’t be all of our doctors and you mostly work with dying people at this point in your career, do you have any recommendations on how to find a good primary care doctor?

You’re right, the US healthcare system is in absolute shambles, and even the most well-resourced among us have a hard time finding a primary care doctor. I recently commented on one of Feed Me’s subscriber chats with my recs (as part of a larger discussion on Oura rings and the downsides of having 24/7 biodata…happy to chat in the comments), which I’ll repeat here in no particular order:

1) go to a resident clinic at a teaching hospital. You’ll not only get an appointment faster, but learners (as a former one myself) tend to be excited to investigate symptoms, explain their rationale behind why they are doing a test (or why not), and are willing to admit what they don’t know. Plus, they are supervised by academic attending docs whose job is to be up to date on good practice and new evidence.

2) Look for recent residency or fellowship graduates who are building their practices–you’ll surely get a faster appointment, and they have actively chosen to go into primary care in this hellish climate. (Jolie note: this is how Sophia helped me find my new PCP in Brooklyn who is one of the best doctors I’ve ever seen.)

Any other resources you recommend?

Yes!! Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital (one of the preeminent cancer hospitals in the United States) has an incredible web guide to supplements (vitamins, herbs, etc)–what they’re purported to do, the evidence behind these claims, and the risks. I love it for the data, but also because it’s a nod to the value of naturopathic and integrative medicine when practiced with the same scientific rigor as allopathic (another name for traditional Western) medicine. And with that, I’ll meet you in the comment section ;).

Whew! I wasn’t lying when I said you were going to learn a lot. Thank you so much, Sophia. As you’d expect from The People’s Doctor, Soph genuinely wants to chat in the comments, so feel free to ask away, complain about the state of US healthcare, share your favorite vitamin fact etc. etc. She will also be around for Office Hours this week.

Also, don’t forget that the exclusive Sachi Skin discount is still active through the end of the month! If you missed my interview with Farah, check it out here.

And with that, class is dismissed! See you next session.

xx,

Jolie

Office Hours Reminder

Join us for Office Hours on Sunday! This exclusive weekly opportunity is available to paying subscribers.

Every Sunday at 5pm EST, I’ll begin a new thread for the week in Substack Chat, where you can ask me anything. Every Monday from 5-6pm EST, I’ll be in that chat live, answering questions for the hour. That way, if you can’t make it, you can submit any time after 5pm Sunday and still get an answer. If you can make it live, join in! You can ask questions in real time and (hopefully) interact with others in class ;)

this was SO good!

this is.... everything i could ever want...